What is the Difference Between Beck Emotional Access Technique and the Meisner Technique?

The Repetition Exercise in Beck Emotional Access Technique (BEAT): Moving beyond an understanding of ‘truth in the moment’ as ‘reaction’

The Repetition Exercise was developed by Sanford Meisner, an American pedagogue who taught some of Hollywood’s leading acting talent. It is a practical exercise which involves focusing the actor’s attention on the world outside of themselves, instead of on themselves. The idea is that in order to act ‘truthfully’ or instinctively, an actor must be able to take the attention off themselves. (I disagree with this simplistic view, but more on this shortly).

Practically, the exercise involves one actor noting simple emotional behaviours in the other actor, such as that they are nervous, or that they are afraid, or that they are hiding and so on.

In the Repetition Exercise, two actors, Actor A and Actor B stand facing each other. Actor A begins by verbalising a sentence which is supposed to be a direct observation of Actor B’s emotional behaviour. The sentence is simple in structure “You are doing X”. For example, “You are nervous” or “you are scared” or “you are uncomfortable” as the case may be. In the exercise, Actor B repeats this observation but from their perspective. It’s important to note here that the exercise isn’t about mindlessly repeating simple statements to each other. Rather it is about transferring ‘point of view’ with each call. For instance, each time the actor repeats the sentence, the actor is supposed to convey the emotional truth of the statement for them, until the other person ‘gets it’.

Imagine Actor A observes that Actor B is nervous. They would say: “You are nervous”. If Actor B disagrees with Actor A’s observation of them, they would repeat this and say “I’m nervous?!” but delivered in such a way as to make obvious the intention that they disagree with Actor A; conveying in other words their POV about it.

The Repetition Exercise doesn’t end. The behaviour called keeps changing, as the other person starts behaving differently. So, as Actor A endeavours to make Actor B get their POV (and vice versa), intention (and emotional behaviour) naturally changes, and this becomes a new behaviour, which is the new observed behaviour. Often, we end up with frustration, anger, disappointment since people keep trying to make the other one get their POV.

The Repetition Exercise when done properly is extraordinary. It allows actors to get in touch with their emotional instrument. And in this fashion, they grow able to disengage speech from feeling. They may utter these words, “you are ignoring me”, but be able to put underneath those words, emotions ranging from the annoyance implied by the statement, to intrigue or ridicule, which are emotions not usually implied by those words.

The upshot of this is obvious. Think for example how through the Repetition Exercise an actor may be able to deliver a host of emotions with the phrase “I love you”. Depending on the actor’s intention, the words “I love you” could be said in different ways to mean: “I am disappointed in you”, “I need you”, “I am grateful to you”, “I am tied to you”, “I am captivated by you”, “I feel trapped by you” and even “I am warning you”. It is important to emphasise that a Meisner actor brings not just tonal intention, but also the requisite emotion to the intention. Through this training, actors are able to bring feeling to any words. One can imagine how helpful it is for an actor to ‘put’ POV/emotion behind the words of the character they play. Being able to imbue words with real ‘emotional stuff’ is the quest of the method actor. Meisner actors are known for their ability to do this work well.

As good as all this sounds, I grew sceptical of Meisner’s work very quickly after I finished my training in it. The first scepticism came from my observation that people are ordinarily very bad at observation. In fact, their observations of others are full of defence mechanisms and particularly, psychological projection. (And as the decades wore on – it is 20years now since encountering Meisner – this has gotten worse. During this time our appetite for saying, sharing or receiving ‘the truth’ has shrunk. Today in fact, we are encouraged to hold onto our feelings and to identify with them, regardless of what has caused them, or what the truth in the moment was. I would go as far as to say that we are encouraged to identify with our defence mechanisms). All this, makes it difficult to work within a Meisnerian framework to arrive at ‘truth in the moment’ in modern Western society.

PSYCHOLOGICAL PROJECTION IN THE MEISNER TECHNIQUE

Imagine this scenario by way of example. If Actor A is a shy person with low self-esteem, they may interpret Actor B’s confidence in the moment as intimidating. And in fact, they often do. They would stand in front of Actor B in the Repetition Exercise and say: “you are intimidating”. Of course, Actor B, who is not intentionally trying to be intimidating in that moment will repeat the statement with the intentionality to indicate surprise, or disbelief etc. Thus, the repetition session would go on with everyone trying to convince the other one of how they feel. As a result, Meisner’s Repetition ultimately leads the actor to feel justified in their psychological projection, which is defensive. In other words, the ego (and its defences) is held supreme and nothing is resolved emotionally. See for example a common interaction in the Meisner Technique exercise:

Actor A: You’re dismissive (POV implying annoyance)

Actor B: I am dismissive! (POV implying incredulity)

Actor A: You are dismissive (POV implying patronising attitude)

Actor B: I am dismissive!! (POV implying offence)

Actor A: You’re offended? (POV implying incredulity)

Actor B: I am offended! (POV implying a vindication)

From above, if Actor B was totally closed off to Actor A, was treating them coldly and with fear, it seems Actor A has just helped them find justification in their behaviour. Which is all very well and good except what happens when they need to embody someone who is completely different to them? Who is, for example, open and warm?

So my first criticism related to Meisner’s reification of the actor’s self. I simply found it a strange notion for an actor and for a methodology of acting to aim at reification of the actor’s self. Isn’t the point of acting to be someone else? And doesn’t it follow from this that actor training should seek to instruct them on how to be other selves? This led me to a second scepticism of Meisner’s work that follows from this.

Meisner was influenced by Freud. According to my own teacher, who was trained by him, Meisner would often refer to ‘eros’ and ‘thanatos’ in his lessons and believed them to be guiding drives of human action. Through the training, Meisner believed that he would enable actors to occupy character instinctively, if he could just get them back to their ‘instinctive’ self. He saw character as a hindrance to instinct.

My disagreement here is not so much with the latter, I too agree that character is ‘cagy’; it locks you out of instinct. It is rather with his methodology, which rests on a not-so-complex understanding of character and human behaviour.

While many would agree that certain drives are ‘instinctive’ or ‘core’ or ‘primal’, people very rarely behave in accordance with these. In fact, much of what we do is a complex negotiation and interaction of competing drives and thoughts, schemas and ideas about who we are and how we should behave. Training actors to more faithfully depict character should involve a more sophisticated methodology that takes this into account.

Meisner got the most important things right! The Repetition exercise attempts to train the actor to attend their focus on the other person while leaving their emotional instrument free to react ‘organically’. The Repetition Exercise however, is not very good at training actors to be someone else, i.e. to embody the other. At the end of Meisner, the actor finds themselves, just like our closed, cold, scared Actor B above. Yet the aim is to be someone else.

The Repetition Exercise brings you back to your own character: takes you back to the primitive, primal, instinctive self. And that self, simply gets in the way of embodying the other. And we are not the same instinctively. We may argue that we all have an ‘eros’ drive (in fact some people would say they don’t), but it is attached to different things.

(I want to say at this point that I don’t believe Meisner thought of the Repetition Exercise in relation to character reification. From what I have read and from what others had said who were taught by him, the Repetition Exercise was intended as a tool to teach actors to listen, to pay attention to each other and to help them get in touch with their POV. And I think it does those things both powerfully and elegantly. The problem for me is this by-product of reifying the actor’s character in the moment, caging them into their own self and into their own source of emotion. And it is a problem for us especially today because our societies have shifted decisively towards understanding the self through the concept of a socio-political identity).

Consider the unremarkable example when an actor, Actor A, has to portray someone who is in love with someone else who is going to be played by Actor B. Imagine Actor A had neutral feelings towards Actor B. (Or consider the more challenging case where they despised them). Even in this regular scenario of Actor A needing to embody a state of being in which Actor B elicits loving, romantic and erotic feelings in them, Actor A (and Actor B) has to do something extra-ordinary to faithfully depict this relationship for real. They have to go outside themselves to do it. So, training actors to get in touch with their POV is only going to help them partly. They actor must do something else to their POV in order to get close to the character’s. They need to step outside of themselves, or move away or beyond their own POV. And Meisner actors, if they reach the final stages of mastery over the craft of acting (which according to Meisner could take 20 years), they can eventually get there. Fast learners do it quicker.

But I felt that the aim of becoming someone else could be reached sooner, much easier, more efficiently, and in a more self-liberating kind of way.

POV REPETITION IN BECK EMOTIONAL ACCESS TECHNIQUE

I found the answer in how to do this, when I took Meisner to the extreme; and possibly one might say took the philosophy to its logical conclusion. We can say that if Meisner wanted to bring actors back to their instinctive self, my aim has been to challenge in them a strong identification with themselves.

Consider how the Repetition Exercise looks like with two BEAT actors, in contrast to the above straight Meisner example:

Actor A: You’re dismissive (POV implying annoyance)

Actor B: I am dismissive! (POV implying incredulity)

Actor A: You are incredulous (POV implying interest)

Actor B: I am incredulous (POV implying vindication)

Actor A: You feel safe in that (POV implying a willingness to be tactful)

Actor B: I do feel safe in that (POV implying a vindication)

Actor A: Safety is important to you (POV implying care)

Actor B: Safety is important to me (POV implying vindication)

Actor A: You feel that it is right (POV implying “I see you”)

Actor B: You see me (POV implying gratefulness/POV implying ‘being touched’)

Actor A: I do see you (POV implying ‘being touched’)

Actor B: You do see me (POV implying ‘being touched’)

Actor A: You are touched (POV implying ‘being touched’)

Actor B: I am touched (POV implying openness/connection)

Often BEAT Repetition Exercises end this way; through acceptance of our behaviour rather than ego-centred identification with it. We use Repetition to arrive often at the opposite of what we started with. As this second encounter shows, Actor B who began the exercise being protective of themselves (cold, reserved, dismissive) comes out in the end, open and connected! The self story transforms. And any ideas they had about who they thought they were (cold, reserved etc) shown to be limiting.

To summarise, in BEAT, my aim is not to get actors to identify with their POV or feelings (which would hypothetically lead the actor to their instinctive self as Meisner hoped); rather it is to ‘notice’ their emotions in the moment. For me the aim is to ‘unravel’ the automatic identification or self story step by step and not to reify it. If an actor feels angry, by bringing attention to their anger – or whatever, most often defensive, emotion they happen to feel – through BEAT they come to a state of non-identification with that anger, such as in the example above. The upshot is the actor ends up feeling the opposite of anger. Or as per above, if they have begun the Repetition Exercise dismissive of Actor A’s intention to connect with them, now within minutes, they are able to open up and feel touched by Actor A’s behaviour.

The effect is so powerful that BEAT actors can flip between extremely different emotions from moment to moment. Good BEAT actors can do this:

Actor A: You’re dismissive (POV implying annoyance)

Actor B: You see me (POV implying gratefulness/POV implying ‘being touched’)

Actor A: You are touched (POV implying ‘being touched’)

Actor B: I am touched (POV implying openness/connection)

In other words BEAT actors go from one feeling to its opposite within moments.

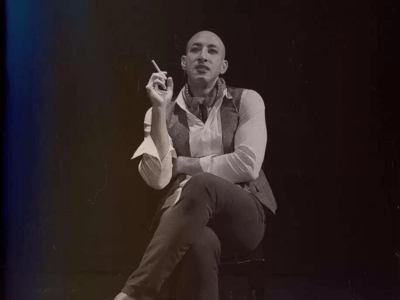

Here are examples from our classes with some good BEAT actors doing this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UdkMiMPNgUghttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zMSjRsW_7pEhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XSi0BaX7MDo

BEAT ACTORS ‘SHIFT’ BETWEEN CHARACTERS FLEXIBLY

BEAT actors are also taught to directly shift not only their moment to moment POV, but also their whole framework. They can become other characters, by shifting their frame of reference/the character’s whole POV system which we call the character’s POV about the world.

Actors who have successfully understood the concept and are able to do this work experience the freedom of not being bound by an identity. They are fluid in this sense. This does not meant that they lose themselves or their identity! On the contrary, they become grounded, grow in presence and confidence. It means rather, that they are able to shift their identity in the performance, moving into the character like acrobats. BEAT actors experience character and identity as a complex but restrictive framework. And they experience a sense of self that is not limited by this restriction.

This understanding of character as a specific framework which restricts experience in particular ways, is very freeing for BEAT actors. In our practice we have found that students are empowered to see things from a different perspective at a deep level. Importantly though, they BEAT actors able to embody the emotional world of other characters with ease.

I feel this leads to empathy. True empathy. Not empathy that comes from the head or from some decision or from some social or political obligation to do it. Rather true acceptance of how the other feels and who they are.