Acting training has long been a battleground of ideas, philosophies, and methods. Ask ten actors about the “best” method, and you’ll get ten different answers – often delivered with near-religious fervour.

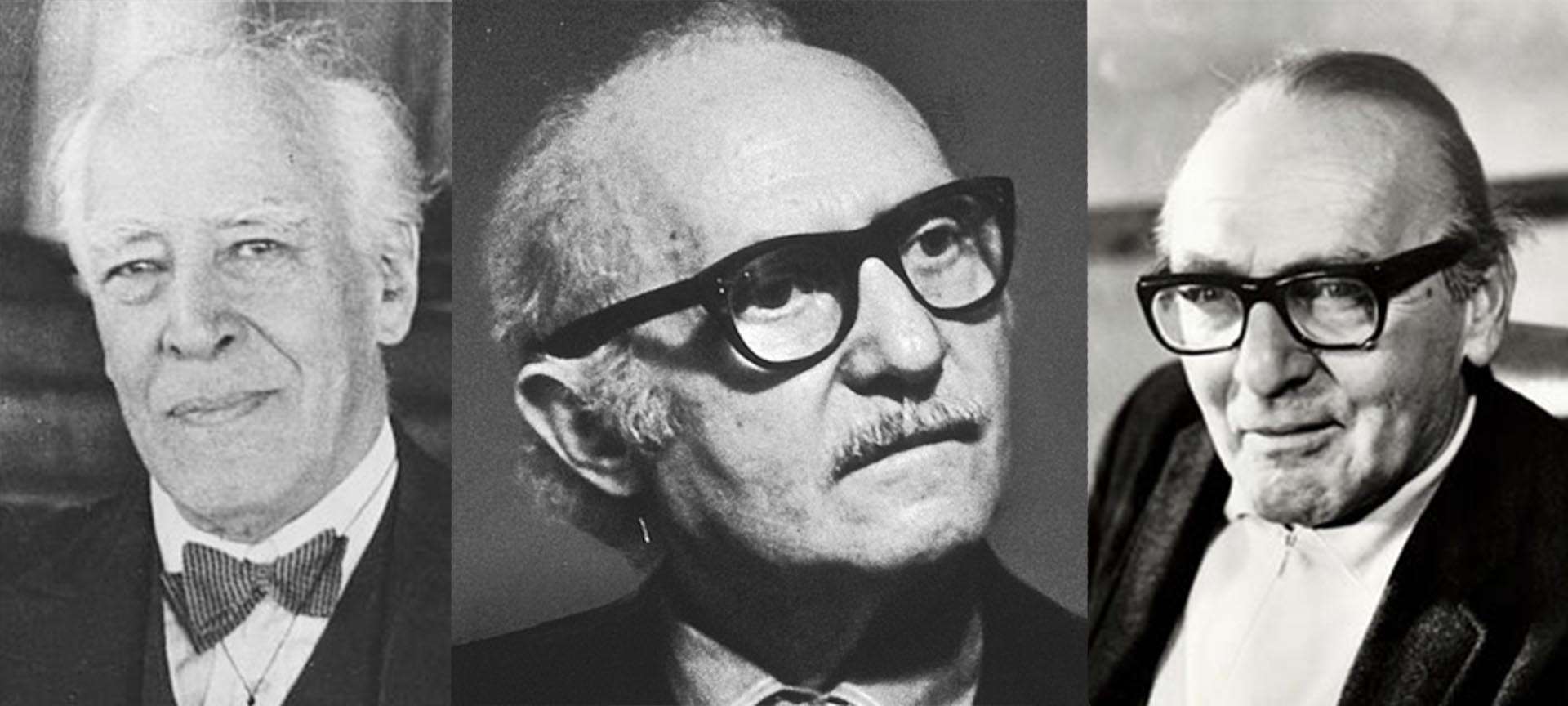

So what is the best method of acting? Is it Chekhov, with his focus on imagination and psychological gesture? Adler, who championed circumstances over personal memory? Strasberg, the father of the Method? Or Meisner, who taught us to live truthfully under imaginary circumstances?

The truth is – there is no single best method. Each school of thought offers something unique, and each has limitations when applied rigidly. To explore this, let’s take a closer look at four of the most influential techniques in modern acting training. Along the way, we’ll ask:

- What does each method give the actor?

- Where do they fall short?

- And perhaps most importantly: how might they be combined to create a craft that is instinctive, alive, and personal?

Stanislavski: The Root of it All

Before diving into Chekhov, Adler, Strasberg, and Meisner, we must acknowledge the source: Konstantin Stanislavski. His system laid the foundation for all four of these approaches.

Stanislavski emphasised psychological realism, objectives, and truthful action. He asked actors to pursue what their character wants, to live through given circumstances, and to approach performance as life lived truthfully on stage.

His influence can’t be overstated. Without Stanislavski, the four methods we’re discussing today would not exist. But while his work forms the soil from which others grew, it is the branches – Chekhov, Adler, Strasberg, Meisner – that actors often find themselves debating.

Michael Chekhov: Imagination and Gesture

Michael Chekhov, a student of Stanislavski, broke away to forge a method rooted in imagination, atmosphere, and physicality. He introduced the idea of the psychological gesture – a physical movement that embodies a character’s essence and unlocks emotional truth.

Chekhov believed that actors should avoid mining their own personal trauma and instead access performance through imagination. By embodying archetypes, atmosphere, and gesture, the actor becomes a vessel for creativity larger than themselves.

Strengths of Chekhov

- Frees the actor from being trapped in personal memory.

- Builds strong physical presence and embodiment.

- Encourages creativity and archetypal exploration.

Critiques of Chekhov

- Some actors find it abstract or difficult to apply to naturalistic work.

- Psychological gestures can risk becoming external “tricks” if not fully internalised.

- In film, subtlety is essential – Chekhov’s physical emphasis can overwhelm the camera if unchecked.

In a world dominated by naturalistic film acting, is there still a place for archetype and gesture? Or might Chekhov’s imaginative approach be exactly what keeps performances from becoming too small, too muted, too safe?

Stella Adler: The Power of Imagination

Stella Adler trained with Stanislavski and clashed with Strasberg at the Group Theatre. Where Strasberg leaned on personal memory, Adler argued for the power of imagination and circumstances.

For Adler, the actor’s job was not to dredge up their own past but to expand their imagination so they could inhabit lives utterly unlike their own. She taught her students to study the world – art, literature, history – to fuel their creativity.

Strengths of Stella Adler Technique

- Encourages actors to live fully in the character’s world.

- Expands an actor’s range beyond their personal experience.

- Produces performances that are rich, layered, and connected to text.

Critiques of Adler

- Some actors feel “cut off” from emotional immediacy without personal memory work.

- The approach requires strong imagination and discipline – not all actors find it natural.

- Can veer into intellectualisation if not grounded in body and instinct.

Is the actor’s job to reveal their own truth, or to transcend themselves in service of the character?

Lee Strasberg: The Method

Lee Strasberg took Stanislavski’s early work on emotional memory and ran with it – perhaps further than Stanislavski ever intended. His “Method” became infamous: actors digging into their own pain, reliving traumatic memories, and using personal experience to power performance.

Strasberg trained generations of American stars – Brando, Pacino, De Niro. His legacy is undeniable. But his method is also one of the most hotly debated.

Strengths of Lee Strasberg Method

- Produces raw, personal, emotionally charged performances.

- Helps actors access deep reservoirs of feeling.

- When mastered, creates extraordinary intensity.

Critiques of Strasberg

- Risk of emotional harm: actors re-traumatising themselves.

- Can lead to self-indulgence, with actors disappearing into their own feelings rather than connecting outward.

- Sometimes prioritises “emotion” over “action” – forgetting that acting is doing.

Should acting demand the actor’s personal wounds, or should it offer a safe space to create emotion without reliving trauma?

Sanford Meisner: Truth in the Moment

Meisner rejected Strasberg’s reliance on memory and Adler’s intellectualism. He defined acting simply: living truthfully under imaginary circumstances.

Through repetition exercises and impulse work, Meisner trained actors to truly listen, respond, and stay alive in the present. His work builds instinct, connection, and emotional truth.

Strengths of the Meisner Technique

- Develops spontaneity and presence.

- Encourages deep listening and connection.

- Builds instinctive performance rather than forced emotion.

Critiques of the Meisner Technique

- Early repetition exercises can feel mechanical or alienating to some actors.

- Risks overemphasis on reaction at the expense of character construction.

- Without guidance, actors may confuse instinct with lack of discipline.

If you are not truly present, if you are not truly responding – are you really acting at all?

Acting Methods Compared – Which is Best?

So which is best? Chekhov’s imagination, Adler’s circumstances, Strasberg’s emotional memory, or Meisner’s truth in the moment?

The honest answer: none of them in isolation. Each offers valuable tools. Each can limit you if treated like gospel.

At Beck Academy of Dramatic Art, our philosophy is simple: acting is not about formulas – it’s about instinct. The actor’s craft should free them, not trap them. Methods are useful, but they must serve the actor, not the other way around.

Best Acting Technique for Beginners

For beginners, Meisner and Adler often provide the clearest entry points. Meisner helps actors break through self-consciousness and connect instinctively. Adler encourages imagination and range beyond personal experience.

If you’re just starting out, our Foundations in Acting course in London offers the perfect entry point — building confidence, instinct, and technique in a supportive environment.

Beyond Formulas: Instinct and Beck Emotional Access Technique (BEAT)

At Beck Academy of Dramatic Art, we believe that searching for the best acting method can sometimes trap actors in formulas. In truth, methods should serve the actor, not the other way around.

That’s why I developed BEAT — an approach designed to bring the actor into direct awareness of the systems in the body that generate behaviour and the origins of emotion itself.

Where Strasberg asks the actor to relive personal memories, BEAT asks a different question: What if you could access emotion directly, through the body’s own systems, without retraumatising yourself?

Where Adler expands imagination, BEAT ensures that imagination doesn’t stay in the head but flows through the whole body, becoming lived experience.

Where Meisner builds truthful instinctive response, BEAT refines the actor’s instrument so that instinct can move freely — without tension, distortion, or blockage.

The result is a craft that gives the actor both discipline and freedom:

- Discipline, through a deep understanding of how behaviour and emotion originate.

- Freedom, through releasing the body to experience and create authentic emotion in the moment.

In other words, BEAT doesn’t ask actors to chase emotion. It places them directly in the current where emotion is born — giving them mastery without losing spontaneity.

Final Thoughts

The debate over the “best” acting method may never be settled – nor should it be. Acting is too vast, too personal, too alive for one method to reign supreme.

What matters is not the system, but what the system unlocks in you. Each technique offers tools. Each can help you grow. And each has blind spots.

Perhaps the real question is this: How do you build a craft that honours instinct, expands imagination, connects you truthfully, and keeps you safe and free in the process?

That is the work of a lifetime – and that is the work we continue at Beck Academy of Dramatic Art.